‘…both the artist and the scientist are prompted by the same creative urge to find a perceptible image of the hidden forces in nature of which they both are aware’. Naum Gabo

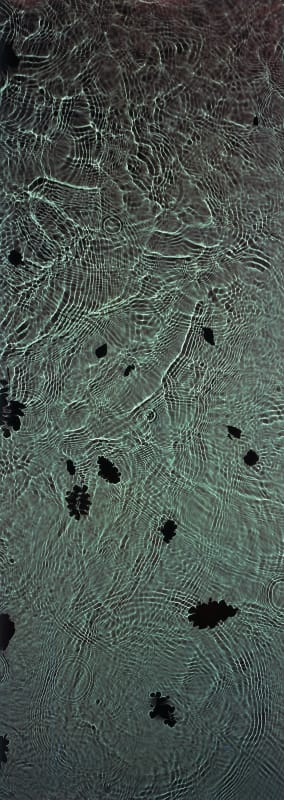

Light sensitive photographic paper is taken at night to a point on the river, or the seashore near the river’s mouth. There it is submerged in the water, and exposed. A flash directed from above the water’s surface is enough to register on the paper what is for that fraction of a second caught between light source and paper: the river’s eddy, flow and turbulence, the edge of the incoming wave as it flows in, the drag of sand behind it. Before that moment of incandescence the paper has been exposed over a longer period to whatever dim light may be refracted and magnified by the water; there is always some glimmer even in the darkest night, starlight or moonlight, or the ambient light from a nearby town reflected downwards from clouds. In each complex and beautiful image is thus inscribed a dual time-scale; moments of dark night time and the brilliant instant of flashlight.

What we have in front of is then, a direct index, the trace of the thing itself whose image we contemplate; ‘indexes establish their meaning along the axis of a physical relationship to their referents. They are the marks or traces of a particular cause, and that cause is the thing to which they refer, the object they signify’. We are looking at an actuality revealed, a moment of the process of reality apprehended; what Wallace Stevens called the ‘incessant creation’ of nature is brought into visibility; a marvellous fact is presented, not represented to the viewer. Presented, it must be said, in a particular way; as a work of art. We are used to the idea of the work of art as the work of conventional signs, marks and gestures, images created with expressive intention; photograms (photographic images achieved without a camera; which is to say, precisely, outside the '‘little room’ of the dark box) are by definition not communicative signs but traces of the real, of the raw material upon which the imagination works. How does Derges’s work differ from that of the scientific investigator using photographic means to examine reality?

Scientists use such indices as the figuring of causes for which they may seek effects, as a clue to the consequences of causation; they are seeking to explain the world, to find patterns in processes. Scientists, like artists, are concerned to trace resemblances. The advanced technologies of photography – microscopic, telescopic, slow-motion, high speed, time-lapse, flashlight, infra-red and ultra-violet – are extensions of the eye which have revealed to us that cosmic, atmospheric and oceanic dynamics correspond to those which may be traced in the microcosmos of the body. These ‘factors of invariance, of similarity in the midst of difference’ we perceive as analogies that enable us to comprehend the harmonics of the universe. The counter-current turbulence in the Devon river configures like the whorl of the spiral nebula; in the apparent chaos of diverse events and constant motion we sense order. Where the scientist seeks to bring into practical understanding what technologies of observation have discovered, the artist has a different purpose; to create and nurture a sense of wonder at the phenomenal world, and to intensify our imaginative experience of it. These photograms of river and shoreline waters and the sky seen through them are at once revelations of a particular and unrepeatable moment in nature, and images that invite our recognition of resemblance and analogy. Framing them and setting them upright, giving them no captions but the date of their making, Derges removes them from the systems of science and places them within the poetics of vision.

The resemblance between things, wrote Wallace Stevens, constitutes one of the ‘significant components of the structure of reality’. This structure is at once something outside us, in the material and dynamic configurations of the world, and inside us an imaginative response to the world, an active construction of personal realities, a collaborative work in constant progress.’There is nothing in nature that is not in us’ wrote Naum Gabo, who thought as deeply as anyone this century about the relation of art to science. ‘Whatever exists in nature, exists in us in the form of our awareness of its existence’. These beautiful images of Susan Derges’s, taken from the heart of a landscape, and revealing to the eye what no eye has seen, are yet strangely familiar. We see, with surprise and delight of recognition, things we have seen before; the variable currents of the river’s ‘watery transparency’, and the flow and drag of shoreline wave, have the look of fire, their elemental opposite; the river’s surface, seen against light, tessellates, lace-like, as ice upon a pane; the edge of a wave, seen from below, seems to imitate the sweep and curve of the coastline upon which it breaks, as it might be seen from the sky above.

In art we have seen this tracing of elemental correspondences most notably in the light, air, fire and watery turmoil in the late, cosmic, paintings of Turner, of which these images also remind us. Of one of these (‘Snow Storm Steamboat off a Harbour’s Mouth’) Turner wrote: ‘I did not paint it to be understood, but I wished to show what such a scene was like …. I felt bound to record it…’ Lashed to the mast Turner was the human eye of the storm, his record of it a brilliant fiction. Beneath the living water of river or shore the light sensitive paper acts as the eye of nature itself, composing in an instant a brilliant fact. Fiction and fact alike are necessary to the adventure of the poetic imagination as it seeks to comprehend a marvellous world.

See: Notes on the Index by Rosalind Krauss, in October the First Decade, 1976-1985 (MIT 1987) The New Landscape in Art and Science, Gregory Kepes (Chicago 1956) Three Academic Pieces by Wallace Stevens in The Necessary Angel (London 1960).

Born in 1955, Susan Derges has established an international reputation over the past 15 years with one-person exhibitions in London, Cambridge, Edinburgh, New York, San Francisco and Tokyo. Her artistic practice has involved cameraless, lens based, digital and reinvented photographic processes as well as video. The metaphors her work has been concerned with encompass subject matter informed by the physical and biological sciences as well as landscape and abstraction.

Derges’ art is an ongoing enquiry into the relationship of the self to the observed that has generated images that combine aesthetic beauty with thought provoking content. Major publications of her work include Woman Thinking river, published in 1998, Liquid form with an essay by Professor Martin Kemp, published in 1999 and Kingswood published in 2002 by Photoworks.